19 Apr The dark side of foster care

On any given day, there are approximately 415,000 children in foster care in the United States. While meeting with two friends a few weeks ago, one of them mentioned a young woman with whom they had recently reconnected after a long break. This girl, Sandra (name changed), had been one of those 415,000 children. As my friend Kenzie shared more, the story quickly touched my heart. Sandra had been in the foster care system in Oregon. Now she was couch surfing, a term used for going from one friend’s home to another, sleeping on the couch, as a way to maintain housing. The story went from complex to almost impossible to miraculous. The young woman was trying to graduate while couch surfing and trying to meet requirement to obtain state support, which entailed the ability to prove a level of stability. This was made all the more challenging by the fact that she had no stable place to live and was finishing high school while depending on the kindness of friends that allow her to couch surf or sleep over a few days at a time.

The miraculous part is that my friend had happened to reach out to this young woman shortly before a big meeting with Health and Human Services, and unexpectedly found herself in the seat of the supportive adult walking alongside Sandra. She was amazed that when the social worker asked Sandra for the names of supportive adults in her life, she was it. She had only just re-entered this young lady’s life.

I can’t imagine what it would be like moving from home to home without real family, even if the home you left was horrible. The alternative doesn’t seem like a great one for most children. I do know there are wonderful foster families, and I know of some amazingly innovative programs that are unleashing the power of family to serve kids in amazing ways. However, we can’t naively believe that this is the solution experienced by the average child in foster care. While most of these children live in family settings, a substantial minority — 1 in 7 — live in institutions or group homes.

We often don’t want to look at the statistics. But we should at least peek…

- In 2014, over 650,000 children in the U.S. spent time in foster care.

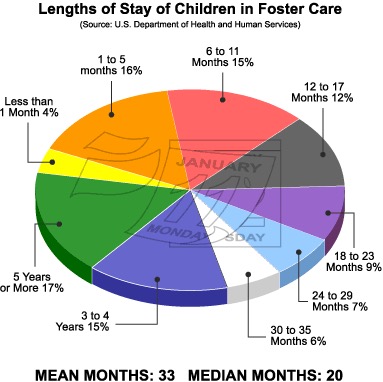

- On average, children remain in state care for nearly two years, and 7 percent of children in foster care have languished there for five or more years.

- Despite the common perception that the majority of children in foster care are very young, the average age is nearly 9.

- In 2014, more than half of children entering U.S. foster care were young people of color.

- In 2014, more than 60,000 children were waiting to be adopted after their mothers’ and fathers’ parental rights had been legally terminated.

The sad reality is that there is so much room for improvement in our system and approach. Sandra was basically abandoned by her foster family when she “aged out” of the program, because they said that they would no longer be paid. That age was moved up to 21 in Oregon in 2008. This was a blessing and a curse. It addressed needed support to older youth in foster care. However, that also put more pressure on the system because the number of foster homes was not increasing. Then, sadly, in December 2015 the state of Oregon was ordered to pay out $15 million in a federal lawsuit filed on behalf of nine children who were sexually abused over four years from 2007 to 2011 while in foster care. The children were among dozens placed in the home of a man named James Mooney before the abuse was discovered. It is truly a horrific tale of abuse of young children ranging in age from 2 days to 3 years. Mooney is now serving a 50-year prison sentence. The interim director of the Oregon Department of Human Services, Clyde Saiki, said that the settlement reflects the agency’s accountability “for failing to ensure the safety of the children in its care.”

Yet it is not the foster system alone that should bear the burden of the children’s care. Sandra aged out or found herself outside of the system, in part, because of measures taken to better screen foster families and protect children from predators like Mooney. I hope those improvements are a good thing, but they don’t likely feel good to Sandra. It is also true that her aging out wasn’t just a legal issue. Rather, it is the result of a lack of homes for teens and young adults. My hope is found in people like my friend, who is modeling something I deeply believe. I believe in the common good, and I believe in our common call to care for children who will spend their entire lives in the system. Certainly, I hope those in short-term care can be returned to safe and loving homes. However, we can’t continue to accept a situation in which children spend their entire lives in foster care until they age out.

We must have an adoptive vision that calls us to become family to these children, and I believe this should be especially true for Christians. Ephesians 1:5 (NLT) says that “God decided in advance to adopt us into his own family by bringing us to himself through Jesus Christ.” If anyone should understand the power of adoption, it’s those of us who follow the Christian faith. Sandra is now building new community — new family — with the support of my friend. I wonder how our systems would be different if our goal wasn’t for children to have a temporary place, but permanent homes. Do I believe everyone can do this? No, but I believe enough people could, and that they could be supported by those who are unable. I’m excited for programs like Safe Families in Chicago that are helping to make this vision a reality.